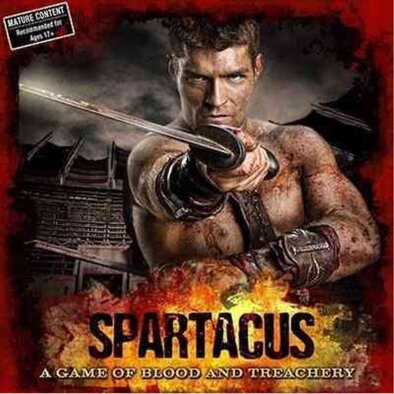

Click here for the previous post in this series. While many board games erase any perceived ethical issues with gladiatorial combat by creating the illusion of universal excitement and consent among fighters, others simply embrace the role of lanista and matter-of-factly have players participate in the Roman slave trade. Most games in this genre at least downplay the reality of slavery by presenting lanistae as “building up a successful school” in pursuit of—what else?—fame and glory. Others focus on the possibility of gladiators earning their freedom. And a few games fully embrace the lurid aspects of Roman culture surrounding gladiators by actively encouraging players to get in touch with the worst aspects of their natures. Most games casually present the role of lanista as manager of a gladiatorial school—with no mention of what this “management” actually entailed. In MUNERA: Familia Gladiatoria (2005), gamers: ...play the role of a lanista, an ancient world entrepreneur who has decided to invest his wealth in the constitution of a Gymnasium of Gladiators with the aim of making it the most glorious of the Empire. You will recruit trainers, armourers, medics and even prostitutes. You will train free men, slaves, criminals and war prisoners to become gladiators and you will bring them to fight in the arenas throughout Italy. You will manage not only the duels, but the whole life of your gladiators: lead your champions to glory! (1) What makes this description interesting is that lanistae are presented as businessmen and entrepreneurs who invest and recruit. While mention is made of “training” slaves, criminals, and war prisoners, that information is placed after more palatable descriptions of recruiting professionals and training free men. It is also followed up with an enthusiastic encouragement to lead your gladiators to glory. The flavor text does not explicitly say how you came to be training these slaves in the first place—because you would have to have purchased them. For Glory, an upcoming game about running competing gladiatorial schools, presents lanistae as cunning: “Blood and sweat spill in the Arena while lanistas, owners of Gladiator schools, machinate to improve their ludus. Their ultimate pursuit... Glory, and to be forever remembered as one of the great lanistas of all time.” All of this pursuit of glory, however, does not explicitly involve slavery. You generate income to purchase cards from a market to add to your deck, but these purchases can include actions and patrons in addition to gladiators. Gladiator: Quest for the Rudis (2016) takes a more frank approach, yet is similarly unconcerned with the human consequences of the players’ in-game actions. In this game, you are a gladiator who is fighting in the arena with attaining glory—of course—but also freedom: Gladiators were mostly condemned slaves sentenced to train, and eventually die, in the arena for the entertainment of the Romans. However, Roman citizens and even Roman emperors opted to fight as “gladiators,” be it for gold or glory. But it was only those slaves whose fates were to live life as gladiators who quested for the rudis. The rudis was nothing more than a symbolic wooden sword, and yet it represented the ultimate prize to a slave-gladiator. To be awarded with the rudis meant fame and possibly fortune, but most of all it meant… freedom. (3) Quest for the Rudis is aimed at realism, and its explicit goal is to recreate gladiatorial combat in a realistic way without creating too many difficult or fiddly rules that would slow down the action. This realism does extend to convincing backstories for the gladiators in the game. Thexos, for example, “was captured in one of the many battles in Gaul, sold as a slave to the lanista of the Ludus Fortuna Baccus and given three things: a new name, armor, and weapons.” Because this game centers specifically on the gladiators’ slave status and their desire to change it by being awarded the rudis, Quest for the Rudis centers the reality of gladiators’ enslavement and incorporates it into their backstories as many other gladiator board games do not. However, this does not necessarily mean that the designer, Jim Trunzo, is entirely sensitive to the situation of the gladiators in this game. In an announced follow-up to Quest for the Rudis that never materialized, entitled Lanista: Gladiator II, players are encouraged to play from the perspective of the lanista who bought, sold, and deployed enslaved gladiators instead. The idea of this game is not to win fights, exclusively, but to earn money and perhaps turn your gladiator school into a full-blown dynastic family business. There are also options for how to roleplay your lanista: The game has over 100 Events that guide the action: outbreaks of disease, complete rules for conducting a slave rebellion, and decisions that go into shaping your persona however your [sic] like. Be an honest businessman and show your loyalty to Rome by reporting those who would fix the games; or bribe Roman nobles to make sure your gladiators will have a primary spot in the next arena contests. Be a cruel taskmaster and impress the Romans and earn Prestige, but possibly pay for your cruelness by inciting your gladiators to revolt. Be a more benevolent Dominus and reward those who help your ludus prosper, but potentially earn a reputation for being soft and easy to manipulate. How you role-play your lanista is up to you. (5) In other words, while the previous game in the series asked players to take on the role of an enslaved gladiator fighting for freedom, the sequel puts them in the shoes of the lanistae who purchased those gladiators—and gives them the option to be a “cruel taskmaster” within the game and to benefit from that cruelty. Meanwhile, being a “more benevolent Dominus [slave master]” can make players look “soft.” Although this sequel was never published, it does make clear that enjoying a game about the pursuit of freedom does not automatically extend to sympathy for, or very much reflection about, the situation of slaves. While Rise of the Rudis is frank about the situation of gladiators and the power that a lanista had over them, it does not impute any particular value judgments to this social situation. Perhaps the most honest game in this respect is Spartacus: A Game of Blood and Treachery, which is based on a popular TV series. In this game, the players are lanistae and their goal is “to become the most influential house in Capua, securing your family’s power for years to come.” (6) This game is blunt about the slaves who run your house to earn money, about the status of gladiators as “exceptional slaves,” and about the trading of “assets” (including gladiators and other slaves) during the Market Phase each turn. (7) During the Arena Phase, in which battles take place, players can choose to pit experienced gladiators against each other, or stronger gladiators against untrained slaves, and then bet on the likely outcomes (“Decapitation” pays two to one). (8) The game also includes intrigue phases and schemes, and is up-front about the fact that none of the players are expected to be good people: “During the game, players will bribe, poison, betray, steal, blackmail, and undermine each other. Gold will change hands again and again to buy support, stay someone’s hand or influence their decisions.” (9) Although the ubiquitous pursuit of glory in the arena is present in Spartacus, the main idea of the game is not honorable at all—players are a bunch of plotting, scheming, power-hungry lanistae who want to win at all costs, human lives very much included. To play this game, and to play well, gamers will have to embrace everything that this entails, including actively trading slaves within the game and often sending those slaves to their brutal, untimely deaths. Regardless of their level of honesty about the situation, games in which players take on the role of lanista are games in which players actively participate in the slave trade—something that typically passes without comment among hobbyist gamers. This leads us to a natural next question: Why do we cackle and take delight in a nasty battle during a game of Spartacus: A Game of Blood and Treachery, but balk at the slave card in Maracaibo? I'll be proposing some theories of my own in the next post. (1) BGG Entry for MUNERA: Familia Gladiatoria (2005) (2) Kickstarter Campaign for For Glory (3) Gladiator: Quest for the Rudis Rulebook p. 2 (4) Ibid. p. 3 (5) Link. (6) Spartacus: A Game of Blood and Treachery Rulebook p. 2. (7) Ibid. p. 1–2. (8) Ibid. p. 12. (9) Ibid. p. 2.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMy name is Liz Davidson, and I play solo board games. A lot of solo board games... Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed