I'm teaching at a new school this year, and I currently spend most of my time thinking about how to be better at my job. Culturally, it's a huge shift from my last school: I've gone from public to private, from economic disadvantage to economic privilege. The changes in student priorities that come with that are staggering. Teenagers are teenagers—they are funny, curious, and engaging, no matter where you meet them. They also worry a lot about stuff, because that's what teenagers do as they find their places in the world. The main difference I have noticed so far, however, is that my new students worry a lot more about grades. I gave my first batch of quizzes today, and the anxiety levels were sky-high. I'm not saying I don't get it. In fact, I was painfully anxious about grades myself when I was a kid. And let's be real—today's teenagers are forced into a competitive world where college admissions are brutal and where more and more is expected of young people. I overheard two students talking in the hallway yesterday, and one was telling the other that she was sad because they never managed to hang out on the weekends. They were too busy with school and with extracurricular activities. I wish I could have told that kid not to worry so much about work, and to go be a kid for once. But I'm not 100% sure that's an option if you want to grow up to go to Harvard. (That shouldn't necessarily be a priority, but I have a fancy education myself and I wouldn't trade it for anything.) The worst part, though, is that all of this performance anxiety has a negative impact on learning. Anxious students do not learn as well as students who are relaxed but engaged. But how do you simultaneously grade students and teach them to relax and enjoy themselves? They would do better and have more fun if they worried less. But if you tell them not to worry, are you lying to them? I've been getting more interested in teaching Latin through comprehensible input—a method that isn't as grammar-heavy as traditional Latin, and that focuses on lowering a student's "affective filter." (If students feel corrected/judged, they clam up.) Rather than teaching grammar and giving the students lists of vocabulary to learn, CI teachers provide them with lots and lots of input—both written and spoken—that is interesting and understandable. There is very little pressure on students to produce the language themselves at first, because they are allowed to do that at their own pace. I'm not yet sure how I want to implement CI or how I would grade student work in a less traditional Latin classroom, but I want the welcoming classroom culture that a commitment to CI seems to promote. Kids in CI classrooms have more fun. Kids who have fun ultimately learn more, get more out of class, and tell their friends—which conveniently leads to higher enrollment numbers. This post isn't explicitly about board games, but I think talking about my work this way also gets at why I think games are so important. Play seems frivolous, but it's actually crucial. In the same way, schoolwork that doesn't feel like work can actually teach you the most. But if you are constantly focused on grades, data, and productivity, you miss all of that stuff. Why do we do that to ourselves? And how do we break the wheel?

0 Comments

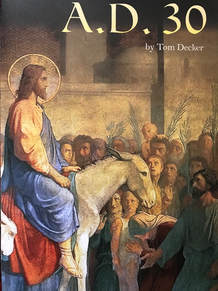

I am a non-religious person with a Ph.D. in Ancient Christianity. This means that, while I lack actual religious faith, I love things that have to do with Christianity. I spend my free time reading the works of Church Fathers. If there is a tchotchke that has a saint on it, I want it. (This is probably why I own a Coptic monk puppet, a Virgin Mary bottle opener, and a small glow-in-the-dark baby Jesus.) Since I am also a board game enthusiast, I had to add A.D. 30 to my collection. A.D. 30, published in 2012 by Victory Point Games, is a solitaire game in which you manipulate the movements of Jesus and his enemies—Caiaphas, Herod, Pilate, and Judas—to orchestrate Jesus' triumphant entry into Jerusalem and to ensure that his betrayal and crucifixion come to pass. You work through a deck of event cards and take actions to ensure that Jesus does not fall into temptation, that he recruits all twelve apostles (if possible), and that his political opponents do not reach Jerusalem before he does. For the record, A.D. 30 treats its subject matter with respect. Tom Decker, the game’s designer, states in his design notes that he wants to “demonstrate to the player the extraordinary set of circumstances that actually took place and were necessary to achieve the historical result and engender the birth of Christianity.” His game includes fourteen different possible outcomes of Jesus’ ministry, ranging from the story we know today to “Satan successfully lures Jesus into temptation and spreads Darkness over the world.” I am more than willing to play a game in which Darkness takes over the world—after all, I face this outcome in H.P. Lovecraft games all the time. But the fact that this game is about Jesus makes this outcome especially uncomfortable for a lot of gamers. Some reviewers keep their focus on whether a game is fun. Ricky Royal, a connoisseur of solitaire games, comments: “For me, a history buff, I’ll happily see it as a game design first, a history lesson second, and anything beyond that is not relevant to this forum.” Others, including Tom Vasel from The Dice Tower, are uncomfortable with several aspects of the game design. In his video review, Vasel objects to the idea of playing as Jesus and especially to the idea that Jesus was at risk of falling into temptation. For me, the temptation cards were the most interesting aspect of the game. (The gameplay itself is just okay.) Within the context of A.D. 30, temptation cards ostensibly represent moments in Jesus' life that Decker viewed as moments of vulnerability for Jesus when he designed the game. When Jesus is located in the desert, he is automatically affected by temptation because that is where he encounters Satan in the Gospels. But there are also events in the Jesus story, as told by the game, that tempt him as you play. These include:  - Teaching in Capernaum (flavor text: "And at once his fame spread everywhere throughout all the surrounding region of Galilee"). - Driving the moneychangers from the temple in Jerusalem - Jesus' meeting with the Pharisee Nicodemus - Jesus' rejection in his hometown - Jesus' rejection in the Samaritan village - The Transfiguration (Elijah and Moses appear and talk to Jesus, Jesus becomes radiant, and a voice in the sky calls Jesus "son") - Pharisees seek to stone Jesus (this event is mentioned in the context of the resurrection of Lazarus) I don't know for sure what Tom Decker was trying to say with his game design choices about temptation. In fact, this is an issue he skirts around in his design notes by saying, “if managed properly, Satan and temptation should not be a serious threat.” But I think that the temptation cards not only invite players to imagine Jesus as a man who experienced temptation, but also to contemplate how events in his life would have made him feel. Some of these events have to do with Jesus' fame or success, and thus possibly his ego. Teaching in Capernaum makes him famous, and his Transfiguration could perhaps be read as ego-inflating. Other events might make Jesus angry, such as his encounter with the moneychangers in the temple and the rejection he faces in his own hometown. A.D. 30 also elegantly reminds us that a game is never just a game—it’s a representation of how we understand and interact with the world. If you believe that Jesus was fully divine and unable to succumb to temptation, this game not only contradicts your beliefs, but forces you to be an active participant in their subversion. When designers create games, they offer an interpretation of the world whether they mean to or not. When you play a game, you at least partially accept the designer’s vision, whether you mean to or not. Because games require your participation instead of merely your attention, they communicate more viscerally than any other medium I can think of. It’s something you don’t think about much when you’re slaying zombies or building spaceships, but it’s there. It just takes a game like A.D. 30 to bring it into sharper relief. |

AuthorMy name is Liz Davidson, and I play solo board games. A lot of solo board games... Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed