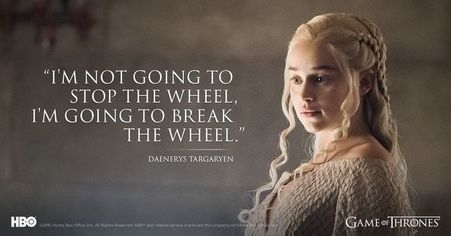

I'm teaching at a new school this year, and I currently spend most of my time thinking about how to be better at my job. Culturally, it's a huge shift from my last school: I've gone from public to private, from economic disadvantage to economic privilege. The changes in student priorities that come with that are staggering. Teenagers are teenagers—they are funny, curious, and engaging, no matter where you meet them. They also worry a lot about stuff, because that's what teenagers do as they find their places in the world. The main difference I have noticed so far, however, is that my new students worry a lot more about grades. I gave my first batch of quizzes today, and the anxiety levels were sky-high. I'm not saying I don't get it. In fact, I was painfully anxious about grades myself when I was a kid. And let's be real—today's teenagers are forced into a competitive world where college admissions are brutal and where more and more is expected of young people. I overheard two students talking in the hallway yesterday, and one was telling the other that she was sad because they never managed to hang out on the weekends. They were too busy with school and with extracurricular activities. I wish I could have told that kid not to worry so much about work, and to go be a kid for once. But I'm not 100% sure that's an option if you want to grow up to go to Harvard. (That shouldn't necessarily be a priority, but I have a fancy education myself and I wouldn't trade it for anything.) The worst part, though, is that all of this performance anxiety has a negative impact on learning. Anxious students do not learn as well as students who are relaxed but engaged. But how do you simultaneously grade students and teach them to relax and enjoy themselves? They would do better and have more fun if they worried less. But if you tell them not to worry, are you lying to them? I've been getting more interested in teaching Latin through comprehensible input—a method that isn't as grammar-heavy as traditional Latin, and that focuses on lowering a student's "affective filter." (If students feel corrected/judged, they clam up.) Rather than teaching grammar and giving the students lists of vocabulary to learn, CI teachers provide them with lots and lots of input—both written and spoken—that is interesting and understandable. There is very little pressure on students to produce the language themselves at first, because they are allowed to do that at their own pace. I'm not yet sure how I want to implement CI or how I would grade student work in a less traditional Latin classroom, but I want the welcoming classroom culture that a commitment to CI seems to promote. Kids in CI classrooms have more fun. Kids who have fun ultimately learn more, get more out of class, and tell their friends—which conveniently leads to higher enrollment numbers. This post isn't explicitly about board games, but I think talking about my work this way also gets at why I think games are so important. Play seems frivolous, but it's actually crucial. In the same way, schoolwork that doesn't feel like work can actually teach you the most. But if you are constantly focused on grades, data, and productivity, you miss all of that stuff. Why do we do that to ourselves? And how do we break the wheel?

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMy name is Liz Davidson, and I play solo board games. A lot of solo board games... Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed