|

Hello, solo gamers!

Many of us are omnigamers who enjoy a wide range of solo games, but I think solo historical and wargames don’t get as much love as they deserve. Every year, I love commenting on the People’s Choice Top 200, but also spend a lot of time complaining about how my favorite games keep falling further down the list, and further out of the public eye. To help more games get their moment in the sun, Brant from Armchair Dragoons and I have partnered up to try something new—we are putting together a “People’s Choice Top 20” list of solo historical games, and we want you to help us out by telling us your favorites! “Historical” is a term we have deliberately chosen to allow a wide array of games to be considered. Your nominees can be traditional wargames, conflict simulations, or games that actively engage with history in some way. (A game with a pasted-on historical theme should not be included here.) By "solo games," we truly mean games that you enjoy on your own. No official solo mode is required—wargamers commonly play multiple sides against each other. Just make sure that if you put a game on your ballot, you do it because you actually enjoy playing it by yourself. If you want to participate, please fill out the Google Form linked here. We will be leaving it open through 12:00 PM EST on August 31, 2023. Once we have closed the form, we will crunch the data, prepare some fun commentary on the results, and publish the list for everyone to enjoy. Thanks for joining us in this new project, and happy gaming!

0 Comments

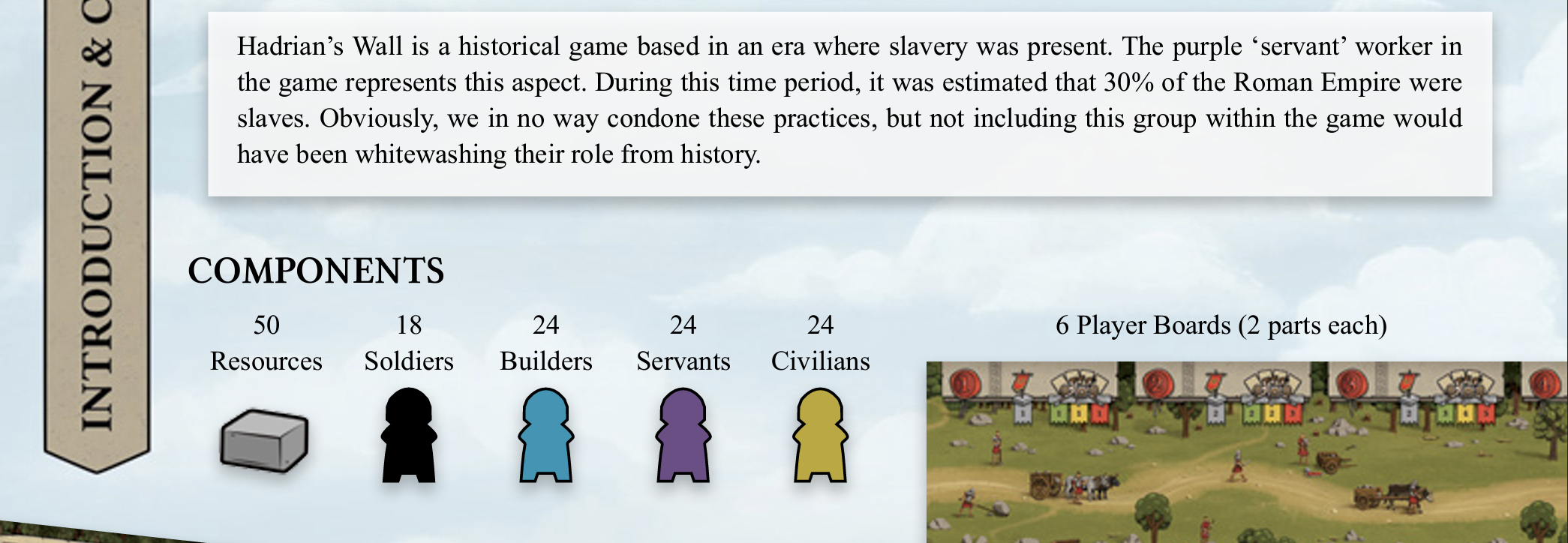

What is a wargame? This is the perennial question from which none of us in the war/historical end of the hobby may ever escape. When I die and wake up in Hell, I will have to sit through an eternal debate with people who are absolutely sure they know what a wargame is, and who only get angrier as their definitions inevitably break down. Why am I like this? I want to preface this discussion with some background about me, which might help you understand where I am coming from. In my experience, definitions have never held up very well. I love talking about religion so much that I got a Ph.D. in Ancient Christianity and teach New Testament in the summers. You could legitimately say I am an expert on ancient religion. But... good luck defining religion in a way that actually works. One of the first major seminar smackdowns we had when I started my Ph.D. program was a session in which we were asked to define religion. Go ahead, try it, and then find out how weird the edges of your definition actually are. If religion is about people having a communal experience and asking God to guide them... you might not even be able to exclude a college football game. My department chair at that time, Katie Lofton, was a brilliant scholar who wrote a book about the Gospel of Oprah. (It's a great book.) One of the students who was nearly finished when I entered my program was Brent Nongbri, who later published a book about religion as a modern concept, not a natural phenomenon. When I was in college, I read Michael Allen Williams' Rethinking "Gnosticism": An Argument for Dismantling a Dubious Category. I did, in fact, rethink Gnosticism—the thesis of the book is that "the Gnostics" as we know them are actually extremely hard to pin down. It seems obvious now, but at the time, my mind was blown. I am sure you are getting my drift, here, so I will stop, but those were very enjoyable years of my life. They also taught me something important: Definitions are messy. They are so messy that overcommitting yourself to one can, ironically, distract you from having a meaningful conversation. What is a Wargame? This definition-related communication breakdown happens among wargamers now, and has been happening for decades. I did not consider myself a wargamer for a long time (there is a tweet from 2018 to prove it), but I do now—with some nuances that I think we are all in the process of negotiating together. If you look at any BGG thread or set of cranky Facebook comments, you will see some slippage between three terms, none of which seems to fully cover the current collective understanding of "wargame." These are: wargame, conflict simulation, and historical game. Wargames are typically understood as simulated battles, usually meant to realistically reflect setting, logistics, etc. This is why games like Summoner Wars are generally not considered wargames, although if you wanted to be difficult about it, you probably could. This is because sci-fi and speculative wargames are frequently recognized as, yes, wargames. Conflict simulation is a term with a bit more slippage. This year's charter for the Charles S. Roberts awards acknowledges this, and explicitly states: "The CSR Awards recognize conflict simulation games, not general board games. However, this charter recognizes that this boundary is often blurry, and this definition includes simulations of non-military conflicts and related historical topics." So, a focus on conflict, but with a historical edge. Unless, again, you're in the sci-fi category which still exists. Then we get to historical games--the area where I primarily see myself. Historical games focus on portraying conflicts, yes. But they can also depict historical settings without conflict, in ways that provide insight into other times and places. For me, this is the richest definition. I also think that as our hobby evolves, "wargames" and "historical games" are getting put into the same general category, and we should work with this trend rather than fight it. The Case Study This brings me to our case study. Two war/historical games came out last year that have the same underlying structure, but are perceived differently, and I find that very interesting. These games are Harold Buchanan's Flashpoint: South China Sea, published by GMT, and Tory Brown's Votes for Women, published by Fort Circle Games.** On the surface, these are very different games. Flashpoint is two-player game about diplomatic and economic conflict between the United States and China as they try to exert control over other countries and island chains in the South China Sea. Votes for Women is a two-player game about Suffragists in conflict with a patriarchal Opposition as the United States decides the fate of the 19th Amendment. However, both of these games have the same structural underpinnings. They are card-driven games, or CDGs, where players use cards that represent historical figures and events. In both games, the cards are used to place cubes and grapple for area control. Both have a common ancestor in Jason Matthews' Twilight Struggle, which has itself gone through the process of being acknowledged as a wargame, even though its war is cold. Both are about conflicts that stop short of actual war. And yet, they are treated differently. Both of these games were nominated for the BGG Golden Geek awards this year, in the "best wargame" category. Almost immediately, comments appeared about Votes for Women from users who wanted to debate whether it was really a wargame. However, there has not been a similar outcry about Flashpoint: South China Sea. You can absolutely find press about Flashpoint that declares it "not a wargame," but most reviews call it one. Additionally, you will not find entire threads about the matter, or a heated debate about it on BGG. Votes for Women, on the other hand, now has its own special BGG thread. On BGG, Votes for Women is categorized as a political game, while Flashpoint is categorized as both a political game and a wargame. At the same time, Kevin Bertram, publisher of Votes for Women, just published a piece in which he convincingly argues that Votes for Women is a wargame, and it is his work that inspired this blog post. Why this disparity in treatment? I think there are a few reasons, and that all of them are in some way true. Possible Conclusions I won't lie. I do believe that part of the "problem" is that Votes for Women is a game by a female designer, about a topic that focuses on women. We are currently in an era where our discourse is highly polarized, and anything that seems to be "about diversity" is going to get some knee jerk reactions. That said, Votes for Women plays it very straight as a historical game, and I personally respect it for that. I think another reason is that Harold Buchanan is an established member of the wargame community and designer of Liberty or Death, another major wargame (as long as you also consider COIN games to be wargames, which has also been a past debate). Buchanan also published Flashpoint: South China Sea through GMT, an established wargame publisher. It seems natural to categorize his creation as a wargame, because that is already part of his public identity. Votes for Women is a debut by Tory Brown, a new designer. It is also only the second offering from Fort Circle. On top of that, Votes for Women got a lot of press, which means that it was on a lot of people's radars, including people who might not be equally aware of the contents Flashpoint and therefore would not have thought to argue about it. But the primary reason for this mismatch in treatment, in my opinion, is that our understanding of political/historical/war games is in flux and we are still figuring out what to do about it. That is naturally going to lead to some inconsistencies. And it's up to us, as a community of people who play wargames, to collectively decide where we want to go with this. I know there will always be a contingent of traditionalists who want wargames to indicate a specific type of conflict simulation, preferably including hexes, counters, and realistic detailing w/r/t equipment, logistical challenges, etc. But if you are one of them, I would ask: Are the boundaries of your definition really as solid as you think they are? I bet that we can find a lot of awkward edge cases. ;) I personally would like to push for a more inclusive and, in my opinion, future-thinking understanding of what a wargame is. I will admit personal bias on my part, because I think that being more inclusive makes the conversation more interesting. It's not that I don't enjoy more traditional offerings--I do! However, by allowing different gaming formats and foci into the wargaming conversation, we give ourselves a chance to have better, more nuanced discussions about both games and history. As a critic, I want to talk about something more than how a game technically works and whether it is fun. As a new designer, I want my game to be evocative, not just mechanically functional. If we exclude historical games with political and social themes as "not wargames," we also dampen some of the most interesting conversations that our end of the hobby can generate. A more flexible definition is also in line with the way our hobby is actually going. As I have hinted above, our definition of wargame has already changed. COIN games and Twilight Struggle were initially more controversial admits into wargame club, but they are now established members. We are now seeing a proliferation of games that aren't quite "hobby games," but also are not "wargames" in the traditional sense. It is also clear from BGG nominations, game reviews, and even wargame channels that these games do "count." It seems only natural to cover them alongside more standard fare. Pax Pamir and John Company are not traditional wargames, but they are some of the best contributions to the games + history conversation that I have yet seen. I am currently in the process of reviewing Stonewall Uprising, which is mechanically a traditional deck builder but is in its soul a brutal evocation of the struggle for gay rights. Amabel Holland sometimes makes traditional wargames, but it is works like This Guilty Land, The Vote, Nicaea, or Endurance that drive the most intense conversations, whether or not you agree with her artistic visions. These are games by people who play and design wargames, and it doesn't make sense to try to separate them out into a different category. Instead, I believe that these games represent a vibrant future for wargaming, one that flies in the face of claims that the medium is dead, or only for old men who are languishing in God's waiting room. This is a change we should embrace in order to keep our hobby fresh, regardless of our games' mechanical particulars. I also, as a historian, believe that everything we do, create, and care about says something larger about us and about the culture to which we contribute. I do not want to build a culture where we exclude games based on narrow definitions, while also using those definitions as a way to stave off change. Wargaming has already evolved. It is evolving. I'm happy to be along for the ride. Footnote **Full disclosure: I've done work for Fort Circle, including the tutorial for Votes for Women, and I also am involved with SDHistCon and consider Harold Buchanan a personal friend. I know and genuinely like all of these people.  A screenshot from a recent playtest of Night Witches. Even the most experienced players can get themselves into trouble. D: A screenshot from a recent playtest of Night Witches. Even the most experienced players can get themselves into trouble. D: I am well into my first project as a game designer, and I would like to start writing about it more! I will never have this particular experience again, and I'd like to have some good records of what it was like and what I learned from it. David Thompson and I are currently co-designing a game called Night Witches, a light wargame about the 588th Night Bomber Regiment. This was a Soviet regiment that was active during WWII and made up entirely of female pilots who flew harassment missions along the Eastern Front. Our game has what I feel is a very strong core rule set, and we are now building up the campaign, including interesting missions, upgrades, and--the subject of this post--failsafe measures. One of the things that is interesting about designing your own game is that you get to know it better than anyone normally would, which warps your perspective of its difficulty level. David and I have a lot of playtesting left to do, but each time one of us demos Night Witches, we are fascinated by how the new player responds to our game. Some people grok it immediately and play in ways that give us a lot of insight into how we will write the rules, or possibly adjust them to account for newly-discovered edge cases. Others, even if they are brilliant people, do not intuitively pick this game up, probably because they are wired for different types of games. And of course, our game has a luck component to it, which means that you can play brilliantly and still have a rough go. This means that as we build Night Witches, we have to account for a range of players. There has to be enough challenge to satisfy those who figure out how to manipulate our game to the max. But we also need safety nets to catch people who struggle, especially early on when they are still learning the ropes. Games require consequences that correspond with player performance, but you also can't kneecap your players in the first mission and expect them to enjoy (or even bother with) the rest of a campaign. In my day job, I am a teacher, and this brings to mind one of our most popular educational buzzwords right now: Differentiation. Differentiation gets thrown around a lot, but what it boils down to is that you need to offer a range of ways for students to access the information you are trying to teach, and a corresponding range of ways to show you what they know. The goal is for students who vary in terms of academic performance, interests, special talents, etc. to all be able to learn from you and to demonstrate that they have done so. Depending on how it is treated, differentiation can be amazing for teachers to implement and for students to experience. But it can also come off as extra work, or something to nod at but largely ignore. It can seem impossible to add differentiation to a lesson plan when we already have so much on our plates, so many students with so many individual needs.  Volko Ruhnke and Doug Whatley appear to be enjoying Night Witches at CircleDC. Volko Ruhnke and Doug Whatley appear to be enjoying Night Witches at CircleDC. But I find that what David and I are doing with Night Witches is, in fact, differentiation--we are making sure that a range of players are able to access and enjoy our game, and that they can approach it in a way that gives them choices about the experience they want to have. We are offering three difficulty levels with VP guidelines to match, but there is also nothing to actually stop players from sticking with a level of their choice. We have had long conversations about how punishing the game should be, how we can keep the experience fun for two players if one plane is having a tough time (Night Witches can be played solo or cooperatively). But this differentiation is aimed at something other than learning objectives--this is differentiation for the purpose of invitation, an attempt to keep players engaged in and enjoying the world we have created. As a teacher who is asked to differentiate for classes full of diverse students, I think that there is a lot to learn from game design. Educators often talk about student learning as entirely outcome-based. The purpose of the differentiation is the learning objective. Its successful implementation is allegedly revealed in the scores on state exams at the end of the year. However, while learning objectives do matter to us as the adults in the room, they frankly do not matter to the vast majority of students. What students need is to be invited, to be provided with a challenge or with a safety net as the situation requires. Student motivation and engagement are tough subjects to tackle and differentiation is only one aspect of that conversation. But I see the connection between what I'm doing in my off-time and what I am doing at work, and I want to keep reflecting on it. Of course, games are different because their ultimate goal is engagement/enjoyment, and school isn't usually like that. But I often ask myself why that is. Learning is something that should be approached with joy. Play is also the most natural form of learning, for basically every conscious being in nature. Creating a game is a great reminder of that. I think my life as a game designer will ultimately make me a better teacher, as well.  Hadrian's Wall was one of my favorite board games of 2022, even though it was actually published in 2021. Although the game is not "historical" in any true sense, playing it did make me want to do a deep dive. Since then, I've taken more of an interest than anticipated—to the point where I would really like to go and hike that wall! Although I am certainly knowledgable about the Roman Empire and its ways, I am by no means an expert on Hadrian's Wall specifically. What I have been learning is... fascinating. I began my studies with a few questions in mind that were related to how the board game Hadrian's Wall presents the wall and its history. I wanted to know what the border security situation actually was, I wanted to know about the settlements that sprung up along the wall, and I wanted to know who actually did the physical labor that was necessary to make it happen. I did not get conclusive answers on any front, but I did learn a lot, which frankly is par for the course when we are asking historical questions whose answers are limited by scant evidence. I didn't expect my next deep dive to be about slavery. I actually want to write some think pieces about barbarians. But the issue has found its way to me yet again, this time spurred on by an aside from the Hadrian's Wall rulebook: So, according to the rulebook, we are dealing with an "era where slavery was present." This is absolutely accurate. What I initially took issue with was the fact that, after this bleak little historical note, we all go on to refer to these meeples as "Servants" for the rest of the game as if that actually makes this any better. (It doesn't.) What I did not expect to find, however, was a bunch of waffling from ancient historians about whether slaves were involved in the actual work of building Hadrian's Wall. There is no question whatsoever that slaves were present at the wall, especially in the settlements that cropped up alongside it. But did they build the wall? Or, as the game version of Hadrian's Wall suggests, did they quarry the stone? My current answer is that there is a good chance, with no way to conclusively prove it. But it actually took me a lot of effort to get there, which is probably the most interesting aspect of this journey. Early on in my reading process, I decided to do what anyone would do, and asked Google some questions. One of my early hits was the official Vindolanda tourist website, which actually has a question about slavery in the FAQ. The site's official copy states: "No, the Wall was built by the skilled Roman legionary masons, with thousands of auxiliary soldiers providing the labour and bringing the vital building supplies to the construction areas." There is at least some truth to this—the Roman army did complete public works projects when soldiers were not actively fighting. At the same time, methought the Imperialists didst protest too much. So I kept digging. I started with some fairly obvious books, including Adrian Goldsworthy's Hadrian's Wall. Although Goldsworthy doesn't hit the issue head on, he does mention living spaces for slaves who assisted cavalry officers, and notes that "slaves, including many owned by the army itself," would have lived along the wall and performed noncombatant functions (Goldsworthy 77, 82). When discussing general army activities, Goldsworthy writes, "Some of these tasks were performed by army slaves or personal slaves owned by some soldiers, especially cavalrymen, but much was done by the legionaries and auxiliaries themselves" (ibid., 92). So, while Goldsworthy is not willing to straight up say that enslaved people were put to work to construct the wall itself, he feels comfortable concluding that they were present in some fashion. Nick Hodgson, author of Hadrian's Wall: Archaeology at the Limit of Rome's Empire, is also (too?) delicate in his handling of the situation. As he puts it, "It is possible that impressed or prisoner labor was used, perhaps in the laborious tasks of digging the Wall ditch and Vallum or transporting materials, but given the degree of precision required and the difficulties of supervision that this would entail, it is unlikely. Legionaries were proud of their ability to carry out such works at speed, and they would not have found them below their dignity" (Hodgson, 89). He does, however, acknowledge the presence of slaves with the army, and at other points mentions that we cannot rely on time estimates for construction that do not take forced labor into account (ibid., 117). Hodgson's comments absolutely fascinated me, for one reason in particular—we know for a fact that slave labor did not necessarily mean unskilled labor. Being an enslaved person in ancient Rome did not imply that a person was uneducated or not a specialist in some way. Slaves did a lot more than manual labor—they taught Greek to Roman children, they performed advanced accounting, and could even act as doctors. There is basically no job in the Roman world that a slave could not perform. Hodgson is perhaps a little too protective of the legionaries' pride. The Roman Emperors themselves were often criticized for elevating their freedmen to powerful positions within the Empire. As a result of further digging, I found two more sets of information. I first stumbled across Morris Silver's article, "Public Slaves in the Roman Army: An Exploratory Study." While the article contained many interesting details, what was more interesting is how little we actually know. It's pretty clear that the army owned slaves, and that they could hold several different jobs, but the exact extent of their involvement is unknown. The second was that according to The Construction of Hadrian's Wall, written by a stonemason who then studied the classics, the actual building work at Hadrian's Wall is functional—but not indicative of the proud and skillful work to which Hodgson alludes. According to Hill, with more training the wall could have been better, but "this was regarded as unimportant, hence the ill-worked, half-finished stones which are typical of milecastle and fort gateways on the Wall. Perhaps even more relevant than the level of training is the obvious lack of care about the appearance of the finished work" (Hill, 128). Although Hill does not rule out the possibility of forced labor at the wall, he does not commit to saying so one way or the other, citing lack of evidence. And in the end that may be what is most interesting about all of my inquiries into Hadrian's Wall. The lack of evidence is astounding given how extensive the wall itself is. We don't have good, detailed army records spanning the relevant time period. We do have inscriptions. We have some writings from Vindolanda, but those largely date to before the construction of the wall (Hodgson, 11). It's not even clear that the wall was built entirely for security purposes—the evidence of alleged barbarian attacks is scant. In fact, the Romans felt comfortable pushing further north immediately after Hadrian's lifetime. The actual border of the Roman Empire in Britain became the Antonine Wall under Hadrian's successor, Antoninus Pius, before receding back to Hadrian's Wall. That, however, is probably the topic of a future blog post. I did, after all, say that I wanted to write about barbarians. ;) So what was the point of all my ramblings? In the context of game talk, despite my dislike of the term "servant," I want to give Hadrian's Wall props for reading the labor situation correctly. And, in some ways, more bluntly than the professionals. We can't necessarily prove that forced labor contributed to the construction of Hadrian's Wall, but everything we know about the Roman Empire and its workings—including its practice of keeping publicly-owned slaves—indicates that we should assume its presence. I am forever fascinated by the clear instinct to smooth over this reality, even among historians. Vindolanda's tourist materials pronounce the wall "clean" of slave labor. Hodgson can't deny the likelihood of slave labor in the army at the wall, but he'd like to think that the legionaries were too proud of their own skills to use it. Goldsworthy acknowledges the presence of slave labor along the wall, but gently avoids the critical pulse point. Why do we collectively do this? As with everything about Hadrian's Wall, there is no single definitive answer. But I think this tendency speaks to the deep wounds that the practice of slavery has inflicted on our own society, and our collective discomfort about that reality. This discomfort has become so intense in the United States that Florida is blocking AP African American studies under the guise that it is "CRT." When doing history, there are always two narratives--our version of "what happened," and the story that we are telling about ourselves by doing history. Our desire to minimize, and even to erase, will define us in the eyes of future historians who look back at us and how we talk about the past. References:

Adrian Goldsworthy, Hadrian's Wall, Basic Books, New York, 2018. Peter Hill, The Construction of Hadrian's Wall, The History Press, Brimscombe, 2010. Nick Hodgson, Hadrian's Wall: Archaeology at the Limit of Rome's Empire, Robert Hale, Ramsbury, 2017. Morris Silver, "Public Slaves in the Roman Army: An Exploratory Study," Ancient Society 46, 2016, 203-240. I love historical games, and I want everyone else to love them too. Fortunately, our hobby seems to be moving in that direction--I am starting to see tons of references to war games and historical games mixed in with conversation about "more mainstream" games, and this warms my heart. This rise in wargame chatter has also led to the renewal of a conversation that happens cyclically in this branch of the hobby. Are wargames controversial? Under what conditions, if any, are we ethically allowed to enjoy them?

I have mixed feelings about these discussions. On the one hand, they mean that people are talking about wargaming and introducing even more people to my favorite part of the board game world. On the other, I find these questions frustrating. Why? Because asking them in this way is indicative of broader--and troubling--attitudes about games, what they are able to do, and where they culturally belong. As game designer Volko Ruhnke mentions in the Punchboard interview linked above, we ask questions about the legitimacy of games in ways that we would not ask them about other forms of media. It is no more questionable to enjoy a wargame about real-world events, including tragic ones, than it is to watch a film or read a book about an intense topic. If you watch the Oscars, you'll know that most critically acclaimed films are often emotionally brutal and focused on challenging aspects of history and culture. Historical dramas about WW2, slavery in America, and even current events are all fair game. We are also very comfortable with watching movies that center human suffering of all kinds. (I'm actually not sure I will be able to watch The Whale because of the intensity of the main character's despair.) The same is true for literature. David Diop's At Night All Blood is Black won an International Booker Prize and is a brutal novel about war, colonization, death, and madness. R.F. Kuang may write fantasy novels, but her storylines are based on real-world history and its atrocities--and The Poppy War was one of the best trilogies I have ever read, while Babel was easily my top book of 2022. I have read and enjoyed a number of books with heavy subject matter over the past couple of years, including Schindler's List, I'll Be Gone in the Dark, and Death in Mud Lick. These were books on serious topics, but I absolutely enjoyed reading them. I'm not saying that you can't question/criticize any of these works. Actually, reflecting and having conversations about art is... part of the point of art. I personally have questions about how much true crime is too much, and I would never assign something like The Boy in the Striped Pajamas in a literature class--not because the subject matter is too brutal, but because I don't agree with how tragedy is depicted in that novel. But I think most of us wouldn't dispute these works' general right to exist. (Unless, of course, you're an enraged culture warrior obsessed with defunding public libraries.) But somehow, when the conversation turns to games, the rules change. What makes games different from other forms of artistic expression? I think that this pivot comes from the same place as my absolute least favorite comment about games, which I am sure many of us have heard before: "Don't take it so seriously, this is just a game! Just have fun already!" This always comes up as a way to dismiss the hard questions... and is thus closely related to the assumption that games can't or don't ask them. Games are absolutely fun, and too few adults--especially in the United States--assign enough value to play. Our work culture teaches us that games are for children, and that they are a waste of time. There are endless self-help books, magazine articles, and YouTube channels always ready to tell you how to use your time better, how not to waste it, how to get more done in the hours allotted to us on this earth. Play is often seen as frivolous. The first time I got a lot of views on a post on this very site, I excitedly told a colleague about it. She responded with, "Liz, you're so smart, why don't you write about something important?" I think I am writing about something important. Sometimes I have to stop myself from apologizing for my love of games, for the fact that I prioritize gaming when I will only be alive for an unknown-but-limited period of time. But when I stop and think about it, I don't regret my choices. Fun is not frivolous. Enjoyment is not childish. Sometimes, "fun" just means "engaging"--and engagement is what games can offer us when we are trying to examine challenging historical topics. To ask whether it is okay to be engaged in this way is to dismiss gaming as a shallow, unreflective activity. Yet, the very things that prompt new wargamers to ask whether historical games are "controversial" are actually part of their value--player engagement and agency pull gamers into the subject at hand, and offer them ways of approaching historical problems that no book or film can provide. This is why games make fantastic teaching tools, even or especially when they focus on controversial subjects. Games are, in fact, taken very seriously in more circles than ever before. University professors who adopt Reacting to the Past see amazing results in their classrooms. Professional wargamers bring real-world problems to life to help military leaders learn more about modern conflicts and possible responses to them. CMU's Center for Learning Through Games and Simulations has begun to publish games that are vetted like other academic publications. And, of course, you should be listening to the Beyond Solitaire podcast to learn about all of this and more. ;) There are a lot of ways to game, and a lot of ways to have fun. But play is the first and truest way to teach and to learn. The real crime would be to dismiss it.  Greenough's sculpture of Washington as Greek God (photo from Wikipedia) Greenough's sculpture of Washington as Greek God (photo from Wikipedia) Click here for the previous post in this series. Over the last few posts, we have seen different approaches to board games about gladiators. Some board games gloss over or elide the reality that gladiators were slaves, while others embrace it, though never quite comfortably. Nearly every game focuses on fights for "glory." Do these games share any other common threads, regardless of approach? I would say yes: Games about gladiators simply do not prick our consciences in the way that games about more recent European colonialism have done. Which leads us to the next question: Why? The most obvious reason is just distance. While the Romans remain part of our collective consciousness in the United States and Europe, we are not actively living the legacy of what the Romans did in ways we can directly point out. Colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade continue to reverberate through our lives in a more immediate way. We still have monuments to slave traders on public display in the United States. People who participated in human trafficking built many of our universities, wrote many of our laws, and put down the roots of inequities that persist to the present day. Large parts of the world still suffer from the effects of being former colonies, from having their borders drawn by foreign powers, from the legacy of the slave trade that taints many of the heroes (?) of our more recent past. The Romans, too, were a colonial power and committed countless abuses against the peoples they conquered. The Romans, too, built their society on the backs of slaves. But it doesn't look like what we think of when we think of enslavement or Empire, because it is so far away from us and from our understanding of the world. At the same time, we look back on Rome as a society to admire. Europe and the United States point very directly to the Greeks and Romans as glorious ancestors from whom we got a lot of our best ideas. In my high school Latin classes, and even in my university ones, I felt connected to Rome in a pleasant, distant way. My textbooks wanted to tell me what was cool and interesting about the Romans, about how brilliant a man like Julius Caesar was—even if he did go to Gaul and commit genocide. Latin still has deep cultural resonance as a "fancy," "classy" language, both in Latin programs and in our popular culture. Many people who learn about Rome do so from a perspective that, purposely or not, is sympathetic to Empire. We are drinking that Roman Kool-Aid and drinking it deep. Our natural sympathy for the Romans must have an impact on how we read the literature they have left behind. Looking at the Roman source material, it is easy to take on the attitudes of the Romans whose words we read rather than the gladiators whose true feelings we will never know—and who were themselves part of Roman culture. For the Romans, slavery was a fact of life, not an atrocity. The value placed on human life, particularly the lives of slaves, was low. For most Romans, no crisis of conscience would have resulted from watching and enjoying a gladiator fight, which means that no crisis of conscience would show up in their writings about the matter. Gladiators’ own tombstones memorialize victories and bemoan defeats, but do not lament the difficulties of their lives. Even sources that are critical of gladiatorial games launch those criticisms from a wholly Roman perspective. When Seneca writes about the impressive nature of the gladiators’ oath, he still despises gladiators as slaves, though his respect for their bravery in the face of death is sincere. The complaints he does voice about the games have nothing to do with ethics. Instead, Seneca is appalled by the brutality of the spectators at gladiator fights, not so much because they enjoy the violence but because of how thirsty they are for it. Murder in public is perfectly fine for a Roman, but loss of self-control is not. This leaves us as modern players, then, with the responsibility of going beyond uncritical acceptance of what the Romans had to say about themselves and their traditions. Gladiator fights are luridly fascinating—on that, both we and the Romans can agree. It is our responsibility, however, to reflect on the roles we adopt when we reenact them. This is not to say that we cannot enjoy a game about gladiators, including particularly cruel games of Spartacus: A Game of Blood and Treachery. But these games also provide us, as scholars, designers, and players, with an opportunity to critically examine what the Romans tell us about themselves—and what our responses say about us. Who do we sympathize with? Who do we believe? The answers to those questions can help us do history, but more importantly they offer us a mirror, if we can meet our own eyes in it.  Click here for the previous post in this series. While many board games erase any perceived ethical issues with gladiatorial combat by creating the illusion of universal excitement and consent among fighters, others simply embrace the role of lanista and matter-of-factly have players participate in the Roman slave trade. Most games in this genre at least downplay the reality of slavery by presenting lanistae as “building up a successful school” in pursuit of—what else?—fame and glory. Others focus on the possibility of gladiators earning their freedom. And a few games fully embrace the lurid aspects of Roman culture surrounding gladiators by actively encouraging players to get in touch with the worst aspects of their natures. Most games casually present the role of lanista as manager of a gladiatorial school—with no mention of what this “management” actually entailed. In MUNERA: Familia Gladiatoria (2005), gamers: ...play the role of a lanista, an ancient world entrepreneur who has decided to invest his wealth in the constitution of a Gymnasium of Gladiators with the aim of making it the most glorious of the Empire. You will recruit trainers, armourers, medics and even prostitutes. You will train free men, slaves, criminals and war prisoners to become gladiators and you will bring them to fight in the arenas throughout Italy. You will manage not only the duels, but the whole life of your gladiators: lead your champions to glory! (1) What makes this description interesting is that lanistae are presented as businessmen and entrepreneurs who invest and recruit. While mention is made of “training” slaves, criminals, and war prisoners, that information is placed after more palatable descriptions of recruiting professionals and training free men. It is also followed up with an enthusiastic encouragement to lead your gladiators to glory. The flavor text does not explicitly say how you came to be training these slaves in the first place—because you would have to have purchased them. For Glory, an upcoming game about running competing gladiatorial schools, presents lanistae as cunning: “Blood and sweat spill in the Arena while lanistas, owners of Gladiator schools, machinate to improve their ludus. Their ultimate pursuit... Glory, and to be forever remembered as one of the great lanistas of all time.” All of this pursuit of glory, however, does not explicitly involve slavery. You generate income to purchase cards from a market to add to your deck, but these purchases can include actions and patrons in addition to gladiators. Gladiator: Quest for the Rudis (2016) takes a more frank approach, yet is similarly unconcerned with the human consequences of the players’ in-game actions. In this game, you are a gladiator who is fighting in the arena with attaining glory—of course—but also freedom: Gladiators were mostly condemned slaves sentenced to train, and eventually die, in the arena for the entertainment of the Romans. However, Roman citizens and even Roman emperors opted to fight as “gladiators,” be it for gold or glory. But it was only those slaves whose fates were to live life as gladiators who quested for the rudis. The rudis was nothing more than a symbolic wooden sword, and yet it represented the ultimate prize to a slave-gladiator. To be awarded with the rudis meant fame and possibly fortune, but most of all it meant… freedom. (3) Quest for the Rudis is aimed at realism, and its explicit goal is to recreate gladiatorial combat in a realistic way without creating too many difficult or fiddly rules that would slow down the action. This realism does extend to convincing backstories for the gladiators in the game. Thexos, for example, “was captured in one of the many battles in Gaul, sold as a slave to the lanista of the Ludus Fortuna Baccus and given three things: a new name, armor, and weapons.” Because this game centers specifically on the gladiators’ slave status and their desire to change it by being awarded the rudis, Quest for the Rudis centers the reality of gladiators’ enslavement and incorporates it into their backstories as many other gladiator board games do not. However, this does not necessarily mean that the designer, Jim Trunzo, is entirely sensitive to the situation of the gladiators in this game. In an announced follow-up to Quest for the Rudis that never materialized, entitled Lanista: Gladiator II, players are encouraged to play from the perspective of the lanista who bought, sold, and deployed enslaved gladiators instead. The idea of this game is not to win fights, exclusively, but to earn money and perhaps turn your gladiator school into a full-blown dynastic family business. There are also options for how to roleplay your lanista: The game has over 100 Events that guide the action: outbreaks of disease, complete rules for conducting a slave rebellion, and decisions that go into shaping your persona however your [sic] like. Be an honest businessman and show your loyalty to Rome by reporting those who would fix the games; or bribe Roman nobles to make sure your gladiators will have a primary spot in the next arena contests. Be a cruel taskmaster and impress the Romans and earn Prestige, but possibly pay for your cruelness by inciting your gladiators to revolt. Be a more benevolent Dominus and reward those who help your ludus prosper, but potentially earn a reputation for being soft and easy to manipulate. How you role-play your lanista is up to you. (5) In other words, while the previous game in the series asked players to take on the role of an enslaved gladiator fighting for freedom, the sequel puts them in the shoes of the lanistae who purchased those gladiators—and gives them the option to be a “cruel taskmaster” within the game and to benefit from that cruelty. Meanwhile, being a “more benevolent Dominus [slave master]” can make players look “soft.” Although this sequel was never published, it does make clear that enjoying a game about the pursuit of freedom does not automatically extend to sympathy for, or very much reflection about, the situation of slaves. While Rise of the Rudis is frank about the situation of gladiators and the power that a lanista had over them, it does not impute any particular value judgments to this social situation. Perhaps the most honest game in this respect is Spartacus: A Game of Blood and Treachery, which is based on a popular TV series. In this game, the players are lanistae and their goal is “to become the most influential house in Capua, securing your family’s power for years to come.” (6) This game is blunt about the slaves who run your house to earn money, about the status of gladiators as “exceptional slaves,” and about the trading of “assets” (including gladiators and other slaves) during the Market Phase each turn. (7) During the Arena Phase, in which battles take place, players can choose to pit experienced gladiators against each other, or stronger gladiators against untrained slaves, and then bet on the likely outcomes (“Decapitation” pays two to one). (8) The game also includes intrigue phases and schemes, and is up-front about the fact that none of the players are expected to be good people: “During the game, players will bribe, poison, betray, steal, blackmail, and undermine each other. Gold will change hands again and again to buy support, stay someone’s hand or influence their decisions.” (9) Although the ubiquitous pursuit of glory in the arena is present in Spartacus, the main idea of the game is not honorable at all—players are a bunch of plotting, scheming, power-hungry lanistae who want to win at all costs, human lives very much included. To play this game, and to play well, gamers will have to embrace everything that this entails, including actively trading slaves within the game and often sending those slaves to their brutal, untimely deaths. Regardless of their level of honesty about the situation, games in which players take on the role of lanista are games in which players actively participate in the slave trade—something that typically passes without comment among hobbyist gamers. This leads us to a natural next question: Why do we cackle and take delight in a nasty battle during a game of Spartacus: A Game of Blood and Treachery, but balk at the slave card in Maracaibo? I'll be proposing some theories of my own in the next post. (1) BGG Entry for MUNERA: Familia Gladiatoria (2005) (2) Kickstarter Campaign for For Glory (3) Gladiator: Quest for the Rudis Rulebook p. 2 (4) Ibid. p. 3 (5) Link. (6) Spartacus: A Game of Blood and Treachery Rulebook p. 2. (7) Ibid. p. 1–2. (8) Ibid. p. 12. (9) Ibid. p. 2.  Click here for the previous post in this series. If you have ever played a game about gladiators, you have almost certainly encountered a mechanism or victory condition that involved crowd favor, fame, or glory. How did we get here, and how does it manifest in our board games? The truth is, whether or not the combatants were willing participants, gladiator fights were exciting. Enormous crowds across centuries of Roman history watched gladiatorial combat with anticipation and delight, and presented the fights this way in their writing and material culture. This is the understanding of gladiatorial combat that most modern gamers choose to adopt, and in the majority of recent gladiator games, the ideas of fame, honor, and glory play a tremendous role both mechanically and in terms of the gladiators’—the players’—overall motivations. Gladiator fights involved risk of life or of serious injury, but based on the flavor text of hobby board games, these risks are both thrilling and honorable. One of the more recent deck builders about gladiators, Carthage, presents combat as a chance to go down in history: The salty sea air mixed with the pungent aroma of sweat and blood burns your nostrils. Having saluted the fickle crowd, you turn to face your opponents. Grim looks of determination meet your gaze. Only one of you will leave this arena. Victory or defeat, history will remember your name in Carthage (1). In this description, the impending battle is bloody, but also romanticized. The point is not to survive in a life of servitude, but to be remembered. The box copy for Ludi Gladiatorii (2015) crows that “Each victory for your ‘ludus’ is a line written in History” (2). The introduction to the rules of Red Sand, Blue Sky: Heroes of the Arena (2011) plays up the death and desperation of gladiatorial combat from the first line: “Gladiator: Just saying the word conjures up visions of vicious combat between desperate men who fought to the death for the amusement of the crowd” (3). However, within the same paragraph, the game trumpets that “Now with Red Sand Blue Sky - Heroes of the Arena you can recreate the glory and splendor of these games on three levels” (4). Even the choice to include the subtitle “Heroes of the Arena” indicates which aspect of a gladiator’s life the designers want to emphasize. Similarly, the 2012 game Gladiators breathlessly declares, “You are a gladiator fighting for Glory in the Roman arena. Savage beasts and vicious warriors are all that stand between you and eternal fame. Defeating your foes is not enough; you must win the crowd’s favor” (5). Games about gladiatorial combat, then, are games in which you fight not to survive, but to feel successful by impressing your audience and even earning a place in history. This general emphasis on fame and glory in the arena does have roots in the original source material, but there are complications—gladiators were in a paradoxical position in society because they were objects of extreme adulation, even obsession, but they were also despised and clearly consigned to the bottom of the Roman social hierarchy. According to Alison Futrell, “By law, gladiators were not entitled to the full range of rights guaranteed to other Romans. They were considered infames, a category of shame that also included actors, prostitutes, pimps, and lanistae, all occupations that involved the submission of the body to the pleasure of others” (6). Glory of a kind was certainly available to gladiators, but it was cut with social shame. The Stoic philosopher Seneca dislikes gladiators, but recognizes the paradoxical way they are viewed. In one of his letters, he notes that there is a certain honor to their complete bodily dedication: “The words of this most honorable contract are the same as the words of that most shameful one: "To be burned, to be chained, to be killed by the sword’” (7). Gladiators were the subjects of art, heroes of Roman pop culture, and sex symbols—it was even rumored that Faustina, wife of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, had an unhealthy infatuation with a gladiator—but there were limits to all that adulation. The Christian author Tertullian, though often curmudgeonly, very accurately sums up the social problem of gladiators: Take the treatment the very providers and managers of the spectacles accord to those idolized charioteers, actors, athletes, and gladiators, to whom men surrender their souls and women even their bodies, on whose account they commit the sins they censure: for the very same skill for which they glorify them, they debase and degrade them; worse, they publicly condemn them to dishonor and deprivation of civil rights…What perversity! They love whom they penalize; they bring into disrepute whom they applaud; they extol the art and brand the artist with disgrace. What sort of judgment is this, that a man should be vilified for the things that win him a reputation? (8) The desire for glory and honor in the arena is one that actual ancient Romans felt, to the point where some aristocrats really did damage their elite social status in pursuit of the adulation of the crowd. But the fact remains over the centuries that gladiators were also social pariahs, without full rights, and in the case of the majority who were slaves, without any rights at all. This is an aspect of gladiatorial life and of Roman culture that has not fully made it into our board games (but stay tuned for the next post). In a way, we as players mirror the Romans who avidly watched gladiatorial games—it is easy to get caught up in the drama, in the excitement of battle, in the narratives of courage and heroism in the face of death. But we do not often show sympathy for the fighters, many or most of whom were not there of their own free will, no matter how much admiration they received. Click here for the next post in this series. References: (1) Carthage Rulebook, p. 1, File on BGG (Accessed 5/25/21). (2) Ludi Gladiatori (2015), BGG (Accessed 5/25/21). (3) Red Sand, Blue Sky Rulebook p.1, also https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/95022/red-sand-blue-sky-heroes-arena (Accessed 5/25/2021). (4) Ibid. (5) Gladiators (2012), BGG Entry, https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/122348/gladiators (Accessed 5/25/2021). (6) Alison Futrell, The Roman Games: Historical Sources in Translation, (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 130. (7) Seneca, Letters 37, Ad Lucilium Epistulae Morales, volume 1-3, ed. Richard M. Gummere (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1917-1925), http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2007.01.0080%3Aletter%3D37%3Asection%3D1 (8) Tertullian, On the Spectacles, 22.3-4, trans. in Futrell.  Click here for the previous post in this series. We're getting to the games now. There are actually several approaches to cover, but I want to confront what feels like the simplest one first: erasure. If you want to have all the fun of a gladiator game and none of the guilt, it is a lot easier to pretend that whole slavery thing was no big deal, or even that it never happened at all. Modern board games do not typically dwell on the fact that gladiators were either slaves or people who had volunteered to accept a low social status. In fact, it is so easy to forget that we as gamers routinely erase that reality entirely from our play, even when enjoying gladiator games that are explicitly set in ancient Rome. A game from 2012 entitled Gladiatori includes flavor text that deemphasizes the reality of slaves as the foundation of gladiatorial combat and plays up the excitement of potential fame and glory: During the Roman Empire, gladiator combat was the most popular form of entertainment. Fighters from all parts of the Empire were included in the shows, including female gladiators, wealthy Roman citizens and in some cases, even aristocrats. Now the time has come for you to gain the immortal glory of the Arena. Fight for your honor, for fame, and for your life! (1) From this description, a player might never realize that most gladiators were slaves. Honor, fame, and excitement win the day. In fact, based on the description from Gladiatori, you might see gladiator fights as focused entirely on shocking exploits by the wealthy, and sometimes women (there in fact were female gladiators, and they caused quite a scandal). The recent game Gladiatores: Blood for Roses (2020) places you in the role of a lanista, or someone who controls a gladiator school and would have bought and sold gladiators in the regular course of business. The game, however, makes that business more palatable by adjusting its language: “To [win], each player bids for the most famous gladiators in history. Hiring these professional fighters for upcoming events will increase your school’s glory and fame and attract bigger crowds to the arena" (2). Players are warned not to spend too much money on “hiring” famous gladiators—explicitly described as “professional fighters”—who don’t earn enough glory for the school in return. By describing what would have been either the purchase of slaves or of contracts in which volunteers gave up their rights as “hiring,” Blood for Roses completely erases the social underpinnings of the gladiatorial combat it celebrates. Aside from this change, however, the trappings of the game are Roman, from the artistic renderings of the gladiators to the Latin words and names sprinkled throughout. This is a game that is very clearly set in Rome, not in a fantasy world— which means the practice of “hiring” gladiators is an erasure of history, not an adaptation of gladiatorial combat to a fictional setting. What makes both of these cases interesting is that they mix in Roman imagery and even actual facts, but they don't include all of the facts. We want the aspects of ancient Rome that we like. But can we really just ignore the ones we don't?  Perhaps the most interesting occurrence of elision of the reality of gladiatorial life takes place in the newly-released game Gladius (2021), in which players are not gladiators or lanistae, but rather spectators who are betting on fights between teams of gladiators—and shamelessly manipulating the outcomes. The game has received praise for its diverse depictions of characters, and there is strong representation of women and people of color among both playable characters and gladiators. The Kickstarter page features a quote from Dr. Seth McCormick, an art history professor, that underscores this point by attempting to ground it in ancient history rather than our modern sensibilities: Thank you for providing further evidence of how diversifying representation in games can broaden players’ perspectives on history. I find that the majority of board games set in ancient Rome adopt a very limited perspective by focusing on war or politics (or both), reinforcing the traditional view that history is the story of Great Men (i.e., rulers and generals). It occurs to me that [Gladius], by emphasizing the importance of spectacle in ancient Roman society (the players are not the gladiators in the arena, but the spectators placing bets), shifts attention to the agency of the masses as the people whose consent actually mattered the most in securing the stability and longevity of the Roman Empire (3). In many ways, McCormick is correct—the Roman world was diverse, and yet is too often depicted as white and male. There are also plenty of interesting aspects of ancient Roman society to study aside from war and politics. But his comments about spectator agency and consent, while well-intentioned, become disturbing when one considers that if Gladius is to be taken seriously as a game about ancient Rome, then the spectators are exercising their agency and consent by placing bets on the bodies of people whose agency and consent were at best limited and at worst completely nonexistent. I haven't spoken with them, but I am 99.99% sure that the designers of the game did not intend for their work to be interpreted this way. But it is the historical reality lurking behind any game with an ancient Roman theme. Many gladiator games on the current market seek to allow us, as modern players, to enjoy the blood, conflict, and spectacle of gladiator games without the guilt. By presenting gladiatorial contests as risks taken by professional fighters, or by implying that they are shows put on by willing combatants of higher social status, or even by focusing on inclusivity among game characters in a way that reflects our modern ideals, we grant intention and agency to our fictional fighters that most real-life ones did not have. By conveniently downplaying the reality that most gladiators were slaves, we make it more palatable to deploy them in the arena, to bet on them, and to take vicious pleasure in their victories and defeats. Is ignoring the historical status of gladiators necessarily a bad thing on board game night? I think that's a matter of what a particular game is trying to say. If you are playing a gladiator game set in a fantasy world, I don't think this historical reality matters all that much—that's why I won't be covering Hoplomachus in this series of posts. I do think that if a game is making factual claims about Rome and about gladiators—and especially if that game prints a blurb from a professor making historical commentary—then questions of accuracy demand serious consideration. Click here for the next post. References: (1) Gladiatori, BoardGameGeek, https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/118567/gladiatori (Accessed May 24, 2021). (2) Gladiatores: Blood for Roses Rulebook, p. 1, https://boardgamegeek.com/filepage/192072/gladiatores-rulebook-1st-edition-final-pf (Accessed May 24, 2021). (3) Gladius Kickstarter page (Accessed May 24, 2021).  Click here for the previous part. Before getting into some deeper game analysis, I'm using this post to lay out what we actually know about the social status of gladiators. So buckle up—it's time for some history! Historically, gladiatorial combat originates with funerary rites, in which slaves were forced to fight to the death in honor of the recently deceased. Although some Roman authors attribute the origins of such fights to the Etruscans, the first recorded Roman gladiator fight is dated to 264 BCE and is recorded in Livy: “Decimus Junius Brutus was first gave a gladiatorial munus, in honor of his dead father” (1). Over time, the games lost their funereal purpose and became larger-scale entertainment, and productions became more expensive and more organized. The ludi, or gladiatorial schools, emerged in response to increasing demand. Gladiators came from three general groups of people: slaves, including prisoners of war; criminals who were condemned to fight in the arena, and volunteers who essentially signed themselves into slavery for a set period of time (2). We also know that gladiators’ demographic proportions changed over time. Gladiators were initially almost all slaves, but by the end of the Republican period, about half of extant tombstones belong to freeborn gladiators (3). This does not necessarily mean that half of all gladiators were volunteers, but rather that of the gladiators who were successful enough to have tombstones erected in their honor (it was not cheap), half were free men. When we talk about "volunteers," it is very important to contextualize exactly what that means. Success as a gladiator was not considered a respectable career goal by any stretch of the imagination. Generally, men who chose this path willingly “were social outcasts, freed slaves, discharged soldiers, or former gladiators who had been liberated on retirement but chose to return for a period of service" (4). There were serious legal consequences for choosing to sign oneself over as a gladiator. For the duration of their terms of service, gladiators, even if voluntary ones, gave up their rights to do as they pleased. As one sourcebook phrases it, “they bound themselves to the status of slaves, surrendering authority over their own bodies to the lanista. They were required to take a formal oath to allow themselves to be disciplined and subjected to physical abuse of the kind associated with training in the ludus” (5). Free gladiators willingly entered a state in which they were not free, in which they sacrificed both legal and physical autonomy. Additionally, gladiators became infames, who "cannot vote, hold public office, or even procure a decent burial plot. No decent person will have social relations with an infamis for fear of being considered one himself, so becoming a gladiator is an irrevocable step" (6). Choosing the life of a gladiator, even if doing so voluntarily, was a sign that someone had nothing left to lose. Ancient sources make much of the occasional aristocrats who participated in gladiatorial combat, but they do that because it is so scandalous. Such participation was generally considered shameful. Emperors were often enthusiastic about the games, especially Commodus, who dressed up as Hercules and competed as a gladiator himself, but this behavior was not considered a positive contribution to his legacy. An obsession with public performances did not reflect well on emperors in any context. Nero’s obsession with performance and public acclaim is considered an embarrassment, and the Roman historian Tacitus writes, “Thinking that he toned down his disgrace as long as he defiled many others, he brought descendants of noble families—who could be bought because of poverty—onto the stage” (7). Of Commodus, the historian Cassius Dio says, “nor did he save anything, but spent it all badly on wild beasts and gladiators” (8). Certainly, some aristocrats became so enamored of gladiators and their tremendous fame that they chose to live out their fantasies of glorious combat in the arena, but this was not normal and it did not garner the respect of their elite peers. What this boils down to is that in a given group of gladiators, at least half—and likely much more than half—of the group was made up of slaves or condemned criminals, while the remainder voluntarily surrendered bodily autonomy in a way that damaged their social status. This remains true when we role play as gladiators in our board games. This is also a fitting time to discuss the role of a lanista. In most sources, you'll see a lanista described as a "gladiator trainer," but this doesn't quite capture the scope of a lanista's work. Within the ludus, or gladiator school, the lanista was boss—even in an imperially-owned gladiator school, the higher-ups seem to have left day-to-day work to him. This is because the lanista's work was considered shameful. Don't forget, hanging around infames like gladiators makes you an infamis yourself. The lanista set the gladiator training regimen, was responsible for rewards and punishments, and set up profitable fights. He also decided when to take on new gladiators, for how much, and from what source. In other words, lanistae actively engaged in human trafficking, and there is just no way around it (9). So, now you know the basics about gladiators and their social status. In the next post, we'll start to look at how gladiators and lanistae appear in modern board games. Click here for the next part. References: (1) Livy periocha libri XVI 16, in Titi Livi ab urbe condita libri editionem priman curavit Guilelmus Weissenborn editio altera auam curavit Mauritius Mueller Pars I. Libri I-X ed. Weissenborn (Leipzig: Teubner 1898), Perseus Digital Library, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0169%3Abook%3D16s (Accessed May 24, 2021). (2) Alison Futrell, The Roman Games: Historical Sources in Translation, (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 120; Fik Meijer, The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport, (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2004), 42-48. (3) Meijer, 44. (4) James Grout, Encyclopedia Romana, https://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/gladiators/gladiators.html (Accessed May 24, 2021). (5) Futrell, 132. (6) Philip Matyszak, Gladiator: The Roman Fighter's Unofficial Manual (London: Thames & Hudson, 2011), 13. (7) Livy, Annales 14.14, in Annales ab excessu divi Augusti, Cornelius Tacitus, Charles Dennis Fisher, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1906). (8) Cassius Dio 73.16, in Dio's Roman History, Cassius Dio Cocceianus, ed. Earnest Cary, Herbert Baldwin Foster, William Heinemann (New York: Harvard University Press, 1914). (9) Matyszak, 58. |

AuthorMy name is Liz Davidson, and I play solo board games. A lot of solo board games... Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed